The Black Space

“I imperfectly draw attention to how seeking liberation, and reinventing the terms of black life outside normatively negative conceptions of blackness, is onerous, joyful, and difficult, yet unmeasured and unmeasurable.” - McKittrick (dear science & other stories)

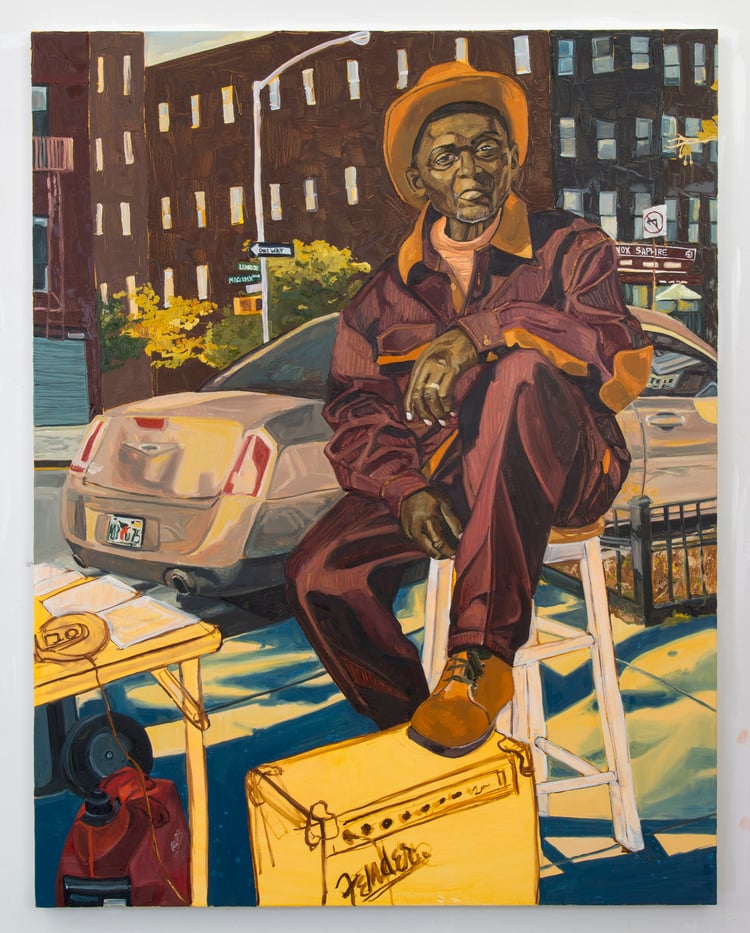

Jordan Casteel, James, 2015, Oil on canvas, 72 x 56 in (182.9 x 142.2 cm)

Collection Dr. Anita Blanchard and Martin H. Nesbitt

Fannie Lou Hamer and Ella Baker at the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party state convention, Jackson, Mississippi, August 1964; photo by Maurice Sorrell (1914–1998)

Johnson Publishing Company Archive. Courtesy J. Paul Getty Trust and Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture.

credit: NMAAHC

....of black joy

who am i

“I believe foolishly perhaps, but sincerely, that I have something to say to the world, and I have taken English 12 in order to say it well.” - W.E.B. Du Bois, Dusk of Dawn p. 39

I am a doctoral student in the Sociology of Education program at NYU Steinhardt. My research is situated at the intersection of the Black identity, education and technology. I am particularly interested in how Black students use technology to make meaning of their identities. At the moment, I am using a Black geographies framework to understand the ethics of radical care in Black place - and space-making despite America’s normalized anti-black logics. As such, I define space broadly to encompass the physical and the virtual.

The Black Space

I started thinking about space- and place-making seriously after indulging Toni Morrison’s novel Sula. In Sula, the Bottom literally means the space that was seen as useless and unlivable to White affluent people, and a place that became critically intricate to the various makings of Black life. The Bottom is at once a site of everyday individual and communal pain, joy, care, strivings, where the tensions of the good, the bad and the ugly coexist. I think about the Bottom as a Black space rooted in the long tradition of Black geographic thought. Black geographic thought centers the production “a black sense of place”, which is often neglected and sometimes treated as non-existent in spatial discussions and practices, to “insist on reimagining the subject and place of black geographies by suggesting that there are always many ways of producing and perceiving space”. (McKittrick & Woods, 2007, p.7).

As a place that was imagined and created into existence, to function as livable, I draw inspiration from the Bottom, to find ways in which Black people in America produced and occupied space throughout the cold war era, where they not only survived but thrived as they simultaneously put their lives on the line to demand equal rights from America. This gallery is a curation of different sites where Black Life occurred during one of the most intense times in American history. By Black Life, I mean the intentional and radical acts of resistance, care, hope and love which vehemently rejected the dominant framing of Blackness as a problem.

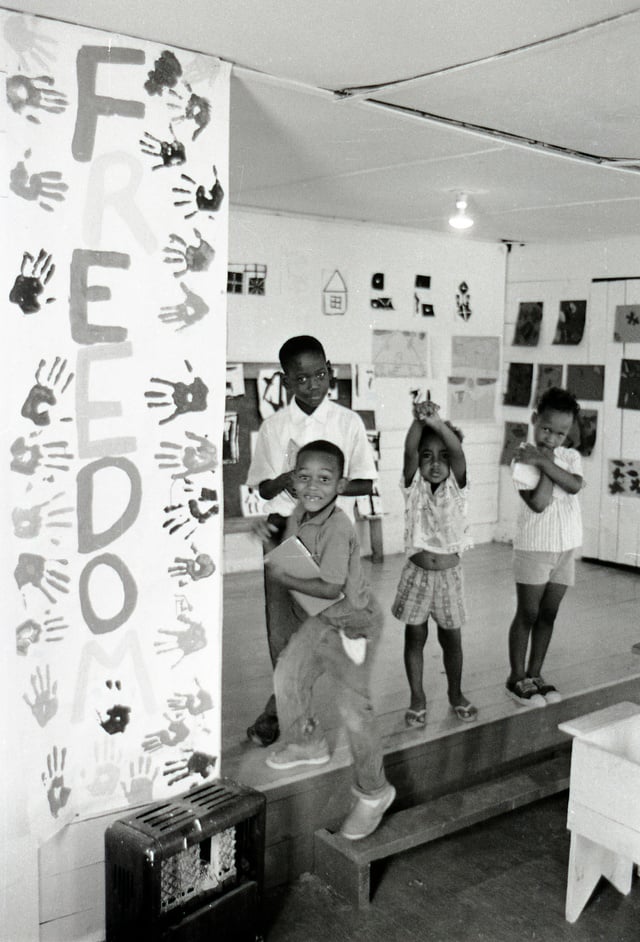

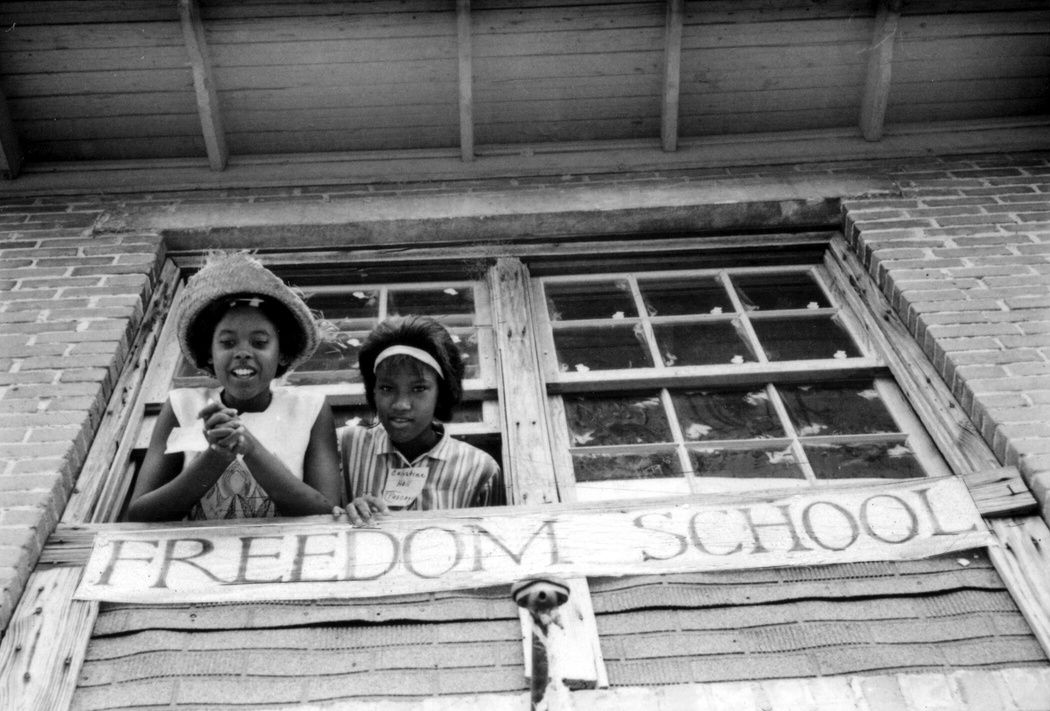

Children visiting exhibit of Freedom School students’ art work at the Palmers Crossing Community Center, Hattiesburg, Mississippi, 1964, Herbert Randall Freedom Summer Photographs, USM. Credit: SNCCdigital.org

Content

01

The Black School

02

Religion & Black Activism

03

Black Family

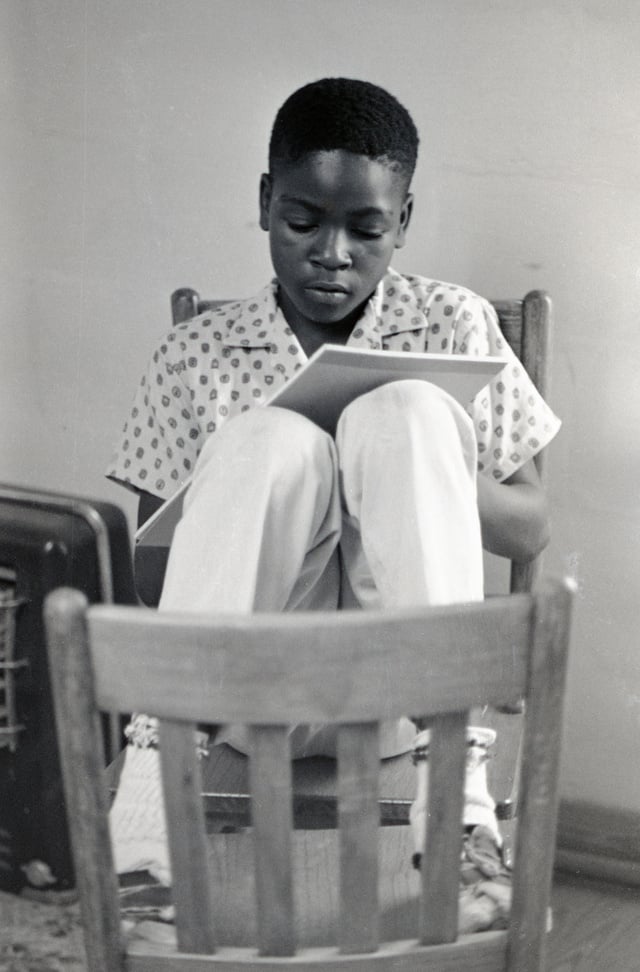

Image 1:

From the Randall (Herbert) Freedom Summer Photographs. Photograph (positive image of a negative) of an African American Freedom School student sitting while writing on a pad resting on his knees during Freedom Summer, 1964, in Hattiesburg, Mississippi. Credit: University of Southern Mississippi

Image 2:

Students read during class in Montgomery, Alabama, April 1939. Marion Post Wolcott via Library of Congress. Credit: Black Teacher Archive

Image 3:

Fenn, A., photographer. (1942) Teacher and Girl Modeling Clay. United States New York New York State, 1942. July. [Photograph] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2017834497/.

In these images, I situate radical care in the positioning of the students and the relationship between them, the objects and the teachers in the shared learning space. The expressions of ease, focus and support in the learning activities evoke a mutually shared respect and comfortability in the spaces they occupy - the small classroom space, the art studio and the improvised learning space where the knees serve as a writing support and the chairs, as foot support.

Freedom Schools

The House of Liberty

by JOYCE BROWN, age 16, McComb

I came not for fortune, nor for fame,

I seek not to add glory to an unknown name,

I did not come under the shadow of night,

I came by day to fight for what's right.

I shan't let fear, my monstrous foe,

Conquer my soul with threat and woe.

Here I have come and here I shall stay,

And no amount of fear my determination can sway.

I asked for your churches, and you turned me down,

But I'll do my work if I have to do it on the ground,

You will not speak for fear of being heard,

So crawl in your shell and say, "Do not disturb."

You think because you've turned me away

You've protected yourself for another day,

But tomorrow surely must come,

And your enemy will still be there with the rising sun;

He'll be there tomorrow as all tomorrows in the past,

And he'll follow you into the future if you let him pass.

You've turned me down to humor him,

Ah! Your fate is sad and grim.

For even tho' your help I ask,

Even without it, I'll finish my task.

In a bombed house I have to teach my school,

Because I believe all men should live by the Golden Rule,

To a bombed house your children must come,

Because of your fear of a bomb,

And because you've let your fear conquer your soul,

In this bombed house these minds I must try to mold;

I must try to teach them to stand tall and be a man

When you, their parents, have cowered down and refused

to take a stand.

(Written for the opening of the

McComb Freedom School on the grass

before the bombed-out private home

at which the school had to be held)

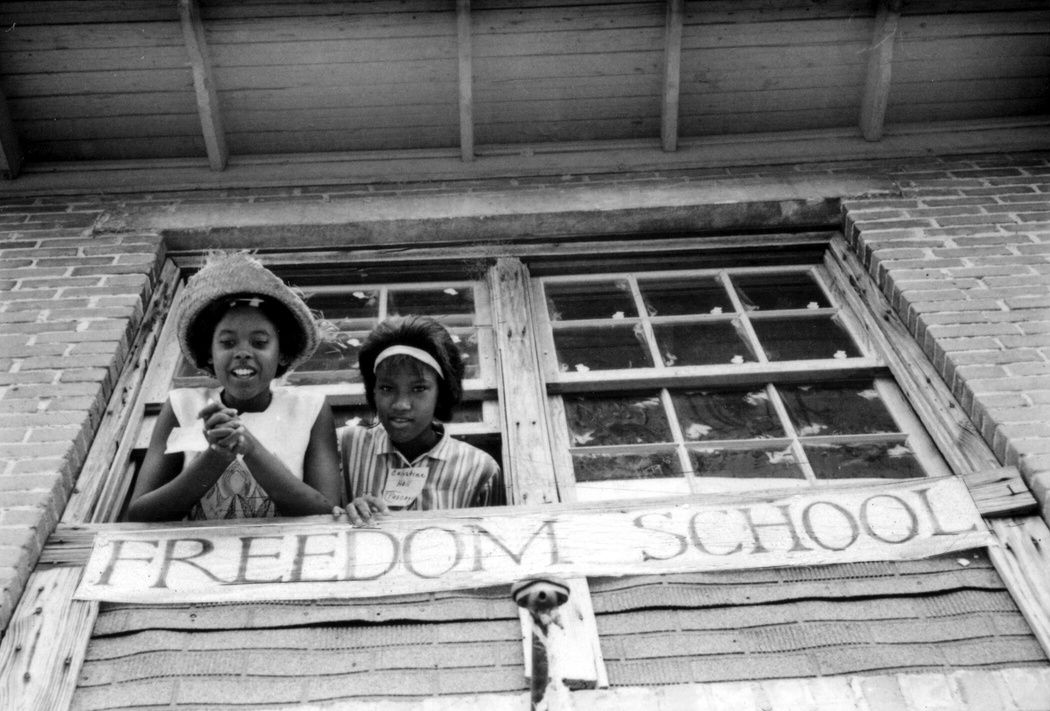

Mississippi Freedom schools/SNCC

Founded in 1964 in Mississippi, the Mississippi Freedom School was born out of the SNCC’s Freedom Summer, a strategic project which sought to end the intense repression of Black civil and political rights in the state. Through SNCC, Mississippi saw a large number of volunteers from the all over the country, specially from the north to help with the civil rights mission. As Charlie Cobb, one of the influential founders of freedom schools put it, “Education should enable children to possess their own lives instead of living at the mercy of others”. (Civil Rights Teaching, np). As such, “a politics of self-discovery, self-expression and self-determination” lied at the center of the pedagogical mission of the Freedom Schools (Perlstein, 2005, p. 36). Eventually, the SNCC would go on to facilitate 41 community controlled Freedom Schools, all over the country, educating Black children and adults.

Cobb’s poetry right on top of his head exudes hope in the practice of doing the difficult, unfathomable but necessary work achieving liberation. The poem evokes a freedom which transcends material benefits, into a place of unease, beyond the fear, where one trusts they can finally be themselves. This imagination lies in the politics of a cultivated care, which acknowledges that liberation work is a continuously tiring work but with inbuilt genuine care for each other, it is easier to anticipate a soft landing on the other side of fear. Here, space is created in the imaginary.

“Ever danced out on a limb

it doesn't always break

and sometimes when it does

you fall

into a grassy meadow”

Charlie Cobb, Spring ‘65

Black Family

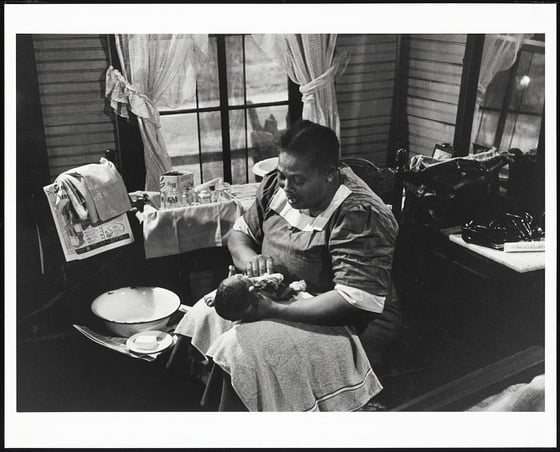

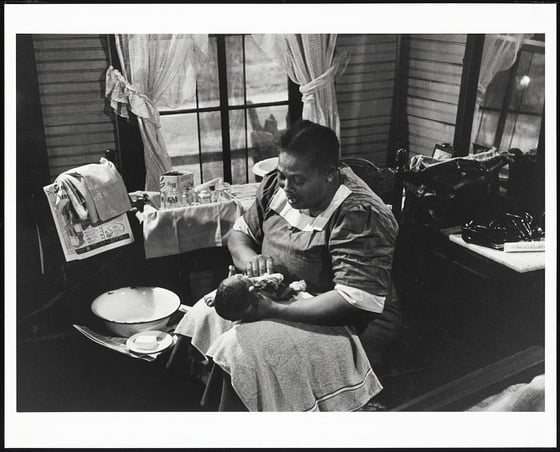

Image 1:

Mary Frances Hill Coley. Untitled (Next day continuing care), 1952. photo by Robert Galbraith (1919 - 2015). Credit: NMAAHC

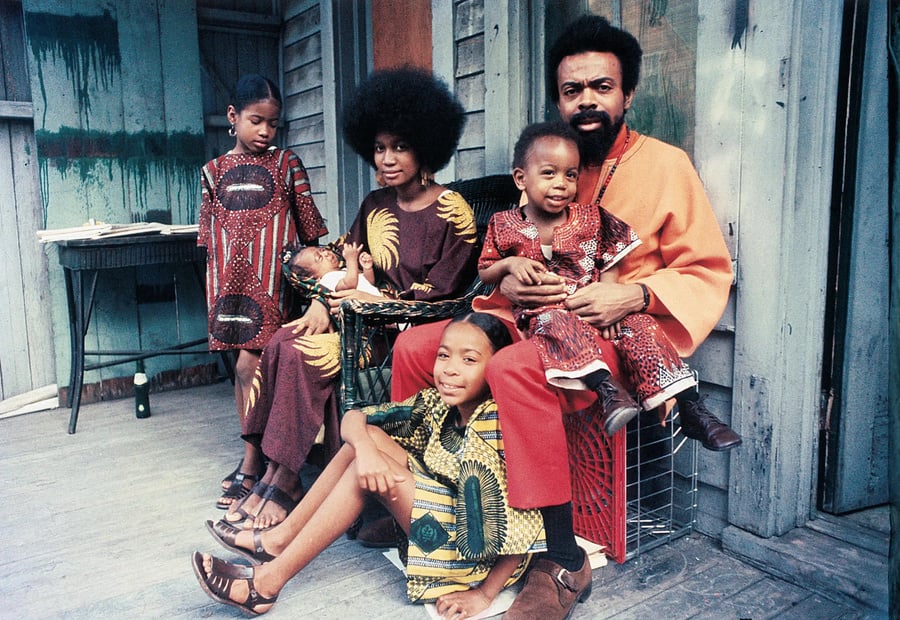

Image 2:

Amiri and Amina Baraka at home with their children, Newark, New Jersey, 1969; photo by Moneta Sleet Jr. (1926–1996). Credit :

Image 3:

Gordon Parks, Anacostia, D.C. Frederick Douglass Housing Project. A family says grace before the evening meal. June 1942, gelatin silver print, image: 19.3 × 24 cm (7 5/8 × 9 7/16 in.), sheet: 20.6 × 25.2 cm (8 1/8 × 9 15/16 in.), The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Museum purchase funded by Mrs. Clare A. Glassell. Credit: nga.gov

“Our history as Black women is the history of women who could build a house and have some children and there was no problem” - Toni Morrison.

How do we tap into our histories of Black homemaking to create intentional, radical communal care to nurture Black children even with the systemic racism, sexism and misogynoir we face everyday? How might centering Black children provide an avenue for Black liberation?

Religion & Activism

For Black people in America, religion has always been tied to liberation - from enslavers, from illiteracy, for community, from poverty, for strategizing, for living.

In 1967, when the House wrongfully accused Rep. Adam Clayton Powell Jr. of embezzlement and excluded him from his seat, the church became a place of solace. The congregation wore “Keep the Faith, Baby” to show that they “see” Rep. Powell. To see here means that they had a deep understanding of America’s systemic discrimination, recognized Rep. Powell’s pain, and that they believed utterly in his innocence. In 1969, Rep. Powell was reinstated after a successful legal battle against the house.

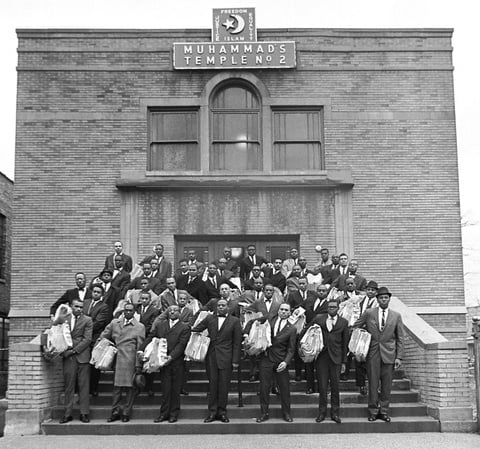

Similarly, the Nation of Islam (NOI) prioritized mass education and economic self-reliance. For instance, Your Super Market, a NOI initiative, almost exclusively supported Black-owned businesses, used their places of worship as learning centers, and distributed newspapers to the Black community.

Congregation members wear “Keep the Faith, Baby” sashes at a church meeting circa 1967, showing support for Rep. Adam Clayton Powell Jr., D-N.Y., who had been stripped of committee chairmanship. Photo by Harry Benson/Hulton Archive via Getty Images.

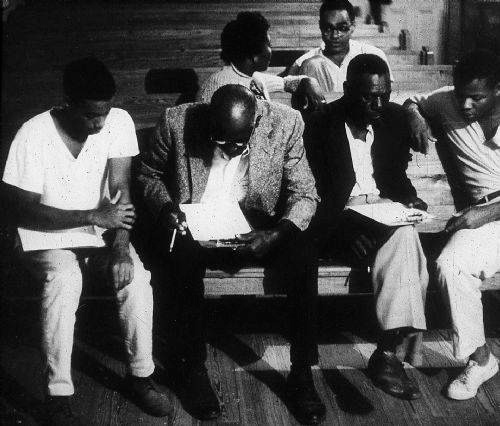

Image 1:

Rosskam, E., photographer. (1941) Untitled photo, possibly related to: Easter procession outside of fashionable Negro church, Black Belt, Chicago, Illinois. United States Illinois Chicago, 1941. [Apr] [Photograph] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2017729488/.

Image 2:

Nation of Islam members stand on the steps of Muhammad's Temple No. 2 with bundles of the NOI newspaper Muhammad Speaks under their arms, Chicago, 1965. Robert Abbott Sengstacke via Getty Images.

Credit: NMAAHC

Image 3:

Charles Cobb, Charles McLaurin, and Bob Moses do voter registration in a Mississippi church, 1962, Danny Lyon, dektol.wordpress.com, located in MFDP Records, WHS. Credit: SNCCdigital

Image 4:

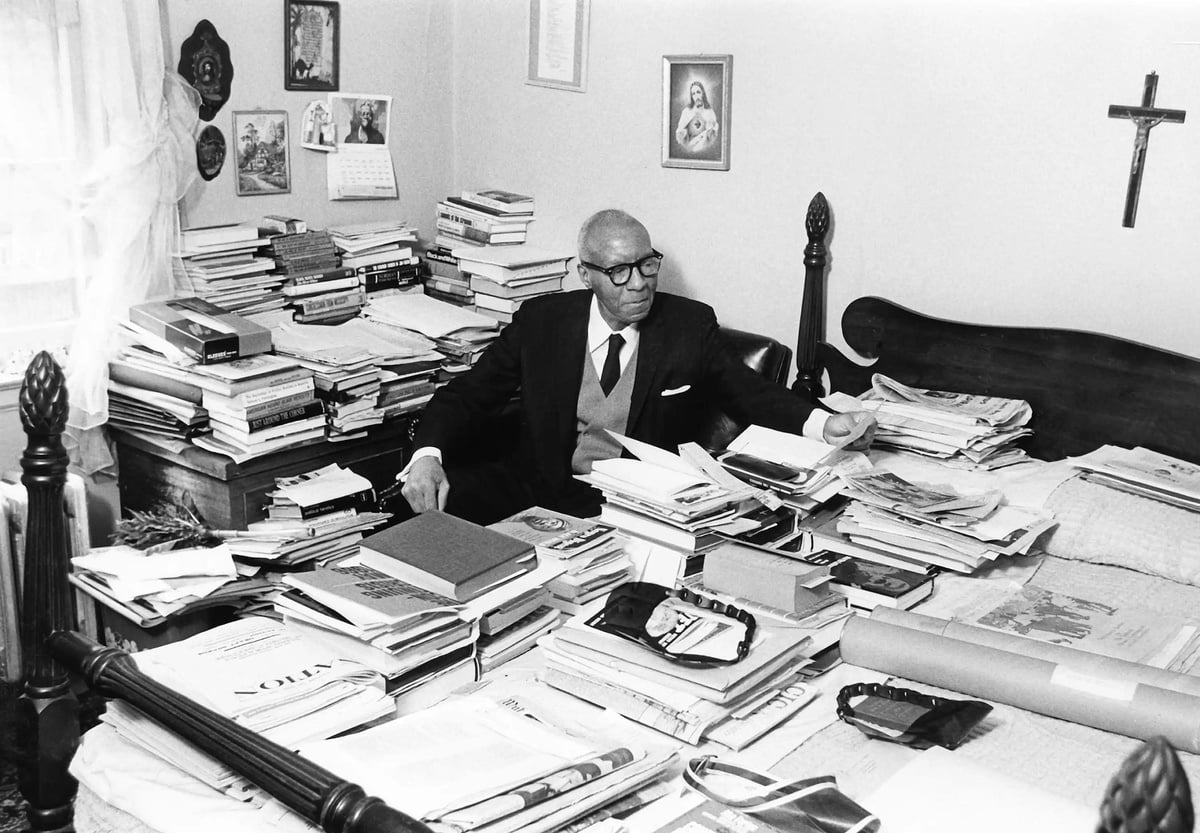

Mahalia Jackson studying music at home, Chicago, Illinois, 1968; photo by Howard Simmons (b. 1943) Credit: Smithsonian Museum

A. Philip Randolph in his apartment, Harlem, New York, 1969; photo by G. Marshall Wilson (1905–1998)

Credit:Searchable Museum

This picture of A. Philip Randolph in his home, where a bedroom functions as a library/archive reminds me of moments in my radical care class, where Dr. Linda Tillman advised that we must expand our understanding of practicing education – that the process of teaching and learning should not always happen in the classroom but also in the churches, community centers, etc. I’m also reminded of Dr. Siddle Walker’s talk about Black educators’ roles in fighting school segregation. She talked about Horace Edward Tate, a Black educator who used his home as an archive that held the Georgia Teachers and Education Association files, at a time when records were being destroyed. In that hidden archive, Dr Siddle Walker found out about the deliberate and intentional network built by Black teachers built to sustain Black education.

All three examples, including the photos in this album are reminders that Black people occupy space strategically to sustain the community, and to leave footprints for future generations, as they find meaning in Black life. I call this a radical act of care which facilitates intergenerational liberatory practices through these “alternative” spaces.